Which hormones cause the body change during the PAUSES?

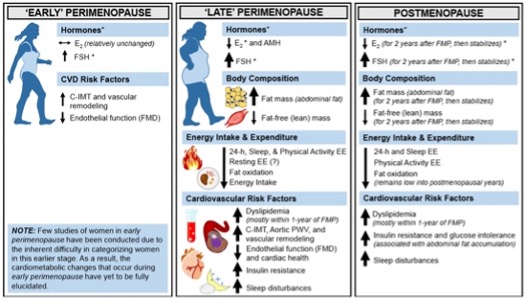

During perimenopause, progesterone is usually the first hormone to decline, followed later by oestrogen. At the same time, androgens such as testosterone may rise slightly. This shifting hormonal landscape plays a key role in how and where body fat is stored.

As a result, many women notice a change in body shape, often moving from a more “pear-shaped” pattern (fat stored around the hips and thighs) to a more “apple-shaped” pattern (fat stored around the waist and upper body).

Before menopause, women typically carry more subcutaneous fat (fat just under the skin, particularly on the hips and thighs) and relatively less visceral fat (fat stored deep around the organs). Subcutaneous fat is generally protective, whereas visceral fat is strongly linked to metabolic and cardiovascular risk.

As discussed in yesterday’s blog, declining oestrogen during perimenopause and menopause drives a shift in fat distribution. More fat begins to accumulate around the abdomen — both under the skin and deeper around the organs. Research suggests that abdominal fat can increase by 20–44%, with most of this change occurring within the first two years after menopause, before stabilising.

Oestrogen plays an important role in regulating fat storage. When oestrogen levels fall, fat is more likely to accumulate centrally. This pattern of fat storage is associated with increased inflammation, oxidative stress, higher blood pressure, unfavourable cholesterol changes, and impaired blood sugar and insulin regulation.

Lower oestrogen also affects mitochondrial function, the cell’s “energy factories.”, which has also been written about in an earlier blog. This can reduce the body’s efficiency at using glucose for fuel, sometimes leading to a temporary dip in energy. Oestrogen also supports thermogenesis (the process of generating heat from energy), so hormonal changes during menopause can influence both energy use and weight regulation.

Visceral fat is particularly problematic because of adipocyte hypertrophy, where fat cells enlarge as they store more fat. These oversized fat cells function poorly and can stimulate the formation of new, unhealthy fat cells. This disrupts appetite regulation, blood sugar balance, fat metabolism, and temperature control.

Both very high and very low oestrogen levels are linked to increased insulin resistance, making fat gain more likely. This is why periods of hormonal fluctuation — such as adolescence, pregnancy, and perimenopause — are considered higher-risk times for changes in weight and body composition.

Supporting Your Body Through These Changes

To help manage these shifts, focus on:

- Low-glycaemic carbohydrates

- Adequate protein intake

- Healthy fats

Together, these support stable blood sugar and metabolic health. If you are still having menstrual cycles, it may also be helpful to include more glucose-containing carbohydrates (such as rice, sweet potatoes, carrots, and beets) in the second half of your cycle, when insulin sensitivity naturally changes.

There is more on this on pages 13, 48-50 of your E book.

Body Fat Changes After Menopause – shift to an “apple/abdominal” shape

After menopause, oestrogen levels drop while testosterone becomes more dominant. This change causes more fat to build up deep in the abdomen (visceral fat).

Because of this hormonal shift, weight is more likely to gather around the waist instead of the hips and thighs.

A Women’s Health study over 5 years found that postmenopausal women had about twice as much abdominal (visceral) and under-the-skin (subcutaneous) fat compared with premenopausal women.